“The company was founded in 2002, with the goal of revolutionizing space technology, and to make human life on the red planet possible. So far, three ships have been built for space transportation.”

“The spaceship is one of thousands of similar ships, with people on board emigrating from Earth, with Mars as the final destination.”

The company, of course, alludes to Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX) and Elon Musk. The second, and very dystopian image is from Harry Martinson’s classic space epic, Aniara, from 1956.

A purely routine start, no misadventures, a normal gyromatic field-release.

Who could imagine that this very flight was doomed to be a space-flight

like to none, which was to sever us from Sun and Earth, from Mars and Venus and from Dorisvale.

An emergency sheer for the asteroid Hondo is followed by other wrecks, and the ship gets off its course and drifts out into the cosmos, with the direction of the Lyre. They are refugees in space, from a devastated planet which they have destroyed themselves.

Our ill-fate now is irretrievable.

But the mima will hold (we hope) until the end.

There are eight-thousand souls aboard, all needing comfort and a circumstance, as they rush through the sea of space, like a bubble in the glass of a bowl, slow and never-ending, without a destination.

I had meant to make them an Edenic place,

but since we left the one we had destroyed

our only home became the night of space

where no god heard us in the endless void.

Besides space–if that is the actual point of interest–it is artificial intelligence that unites Musk and Martinson. It may be surprising to some that I connect them, but their common ground is curiosity. Who are we and where are we headed?

Musk wants to construct science fiction, in reality, like a business project. Martinson made his construction with more secure means, as he built dreams, with poetry as the medium and goal.

“Our ill-fate now is irretrievable. But the mima will hold (we hope) until the end.” Martinson writes, already in the third song. The Mima is never explained, unequivocally, but:

They know that the mima’s intellectual and selectronic sharpness

in transmission is three-thousand eighty times as great

as mankind’s could attain if it were Mima.

The Mima is a machine creature, and she has invented half of herself. She comforts others with images of the lost paradise, but being incorruptible, she also shows images of the future. Then, it is a Cassandra that speaks, she that can see into the future; but nobody believes her. The curse makes these warnings disappear into the empty ether.

In anguish sent by us in Aniara

Our call-sign faded till it failed: Aniara.

Aniara is a tracker, a feeler sent out into the future.

Martinson warns us, but nobody listens.

Though space-vibrations faithfully

bore round our proud Aniara’s last communiqué

on widening rings, in spheres and cupolas

it moved through empty spaces, thrown away.

Harry Martinson released his Magnum Opus in 1956, only a decade after World War II, and when the new arms race had started. We return to the secondary impulses of Aniara, but his interest in technology has been well documented. Sweden was probably a part of the new technological arms race. The first computers in Sweden (BARK and BESK, which were “the world’s fastest computers for a few weeks”) nourished the imagination. Martinson tried to gaze further. Progress threatened to take undesired directions. That fear and legitimate worry lives on.

If we read beyond Harry Martinson’s boyish curiosity for science fiction, some paradoxes exist. His fictitious technical jargon and the breathtaking dimensions of the space adventure crash, with astronomical inconsistencies. The twisted space glides into religious images.

Miman has the features of the kind of artificial intelligence which is expanding today, with neuron networks and machine learning, but there is a great difference. When Miman sees the results of what mankind has committed against itself, and against the Earth, she cries with the rocks. She dies of sorrow. Miman has feelings.

Now, in the name of Things, she wanted peace.

Now she would be done with her displays.

Both space and artificial intelligence feeds the imaginations of both researchers and entrepreneurs, as it does poets, philosophers and people, in general. There are many in pursuit of quick winnings.

Another one of Elon Musk’s initiatives is the idealist company, OpenAI, with the mission of creating friendly general artificial intelligence (AGI). In the big picture, it seems utopian to create AGI, complete or strong AI, with human-like intelligence, and with a conscience, esthetics and reason.

Harry Martinson was self-taught at most things. During the summer of 1953, he saw the Andromeda galaxy in his telescope. This discovery of the galaxy was a moment of inspiration, a deciding impulse for the imagination, a strong experience which was insightful. He dictated the first third of Aniara during a few summer weeks in a poetic discharge, while his wife wrote down the words. His frustration resulted in an artistic therapy session.

The word frustration is often present in Martinson’s writing. He was in despair after World War II, and above all, the most extreme moments of it, with the detonation of the atom bombs above Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Soviet Hydrogen bomb a few years further deepened the feeling of powerlessness.

He received the Nobel prize (1974) for writing which captures the dew drop and reflects the cosmos. In Harry Martinson’s entire output, the love of nature and the Earth are a continuous theme. The wonder of the dew drop fascinated him:

There is an agreement

between the poetry in your heart

and the poppy

written by the wind and signed

by corruption.

Written with the feather of a crane

dipped in the blood of a mayfly.

In the space epic Aniara: an Epic Science Fiction Poem, the Earth remains the central focus. The blue planet is reflected through the cosmos. Aniara is a cosmic tale of humanity at a crossroads.

Martinson sees the global consequences of the destruction of the environment. He plays with the technological progress, which both seduces and destroys. Space becomes a stage for a science fiction adventure. Mankind simultaneously seeks itself and is the threat to everything.

There is protection from near everything,

from fire and damages by storm and frost,

oh, add whichever blows may come to mind.

But there is no protection from mankind.

On board, the anxiety grows. When an answer is perceived to found, there is a realization that the unfathomable has, in fact, expanded further. One day, the chief astronomer makes a speech aboard the Aniara:

We’re coming to suspect now that our drift

is even deeper than we first believed,

that knowledge is a blue naiveté

which with the insight needful to the purpose

assumed the mystery to have a structure.

More than sixty years after its publication, the reader is bedazzled by how ahead of its time Aniara was. There is an artificial intelligence onboard, as an opportunity and comfort; the mima is a telegrator, that invented half of itself. The epic is a call for help before the threat of nuclear weapons–so they cry from stones as did Cassandra. Aniara seeks a safer planet than the one which was destroyed by nuclear weapons.

- - -

In November, 2017, I had the privilege to visit The Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton, USA. The institute (IAS) is, undoubtedly, one of the world’s top facilities for basic research in “the physical world and humanity”. Ever since Albert Einstein’s time there–he was one of the first professors–the most important concepts have been curiosity and surprise. Lone researchers receive an invitation for stints of a few years–or in some cases, for a lifetime–and have no other tasks than being curious. To date, it has resulted in thirty-three Nobel prizes, among others.

The institute is filled with tranquility, surrounded by parks, and is a 30-minute walk from the famed Princeton University. Tradition weighs heavily, but in an inviting atmosphere. Art has been granted space at IAS, which is evidenced, among others, through a special program for artists-in-residence. Since 2016, the composer David Lang has been active among the academic researchers, and was actually the reason for my visit. I was in attendance at his concert with the chamber choir The Crossing.

Here, now, is the perplexing paradox. The institute is like a destination for a pilgrimage, where leading practitioners of science gather. In the guest house, where I was waited on in all conceivable manners, and where I slept in an exaggeratedly large bed, an air of tranquility respires. I secretly toy with the idea that a part of all of this wisdom will remain with me, somewhere... And I do understand that after Einstein, even Robert Oppenheimer has lived here. In fact, it was here, at IAS, where Oppenheimer came directly after the Manhattan project was ended, with the detonations of the first atom bombs above Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August, 1945. Afterwards, Oppenheimer was the head of IAS for twenty years. Einstein lobbied for the project, and Oppenheimer took it in for the win. Here, some of the world’s most prominent researchers–for example, the thirty-three Nobel prize winners–have lived and worked. Even the researchers that were directly linked to the creation of the world’s most dangerous weapon of mass destruction.

- - -

On December 10th, 2017 ICAN received the Nobel peace prize. The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) received the award “for their work in identifying the catastrophic humanitarian consequences for any use of nuclear weapons, and for their groundbreaking efforts to achieve an agreement to prohibit the usage of such weapons”.

ICAN is an umbrella organization for nearly five-hundred grass roots organizations in one-hundred countries. Their most important work is the advancement of the UN treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons, which was adapted in July of 2017, and which now awaits ratification by the UN member states. Neither Finland nor Sweden have signed the treaty. Sweden has impelled the treaty, but has yet to sign it. Within ICAN, five Finnish and fourteen Swedish organizations perform their work.

ICAN was awarded the Nobel peace prize for their counteracting of the scenario that Harry Martinson, the Nobel prize laureate in literature, envisioned on-screen of his own Mima, onboard the Aniara during the summer of 1953.

---

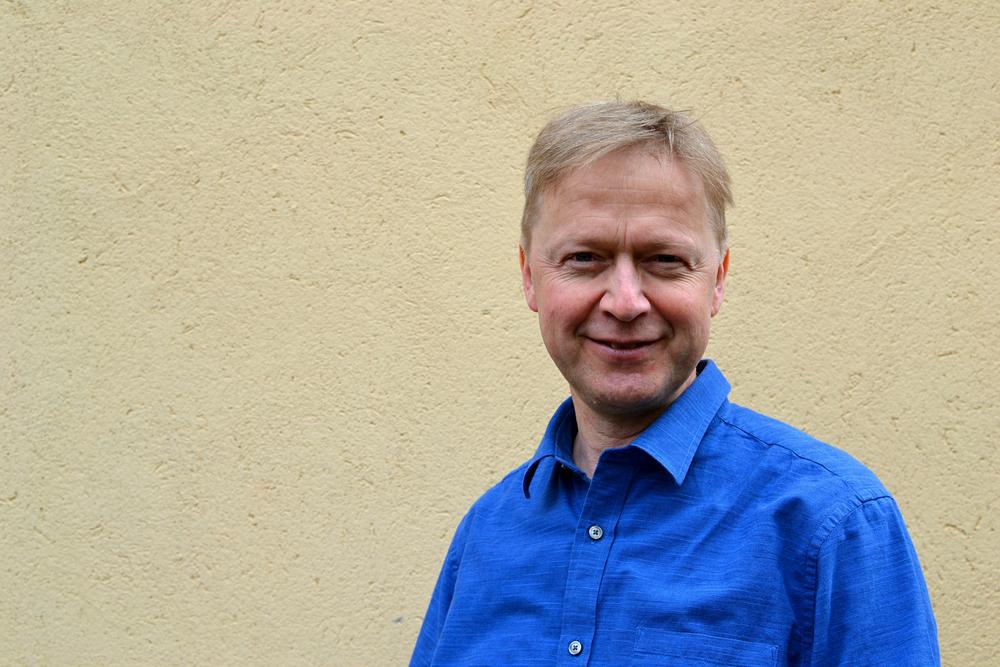

In his book Rauhankone - Tekoälytutkijan testamentti, (in English, approximated, The Peace Machine, a testament of an AI researcher) professor Timo Honkela presents a fantastic idea of how the future global neuron network, consisting of millions of linked computers, supports comprehension between people, and which can negotiate and navigate the meaning of language and the words contained.

His ideas about the Peace Machine and how Artificial Intelligence can contribute to the creation of peace on Earth is based on three pillars. Comprehension of what the other party intends to communicate requires a system of tools for everyday situations which are in place to avoid misunderstanding, the extensions of which can avoid future conflicts and wars. Honkela’s Peace Machine aims to clarify what the individual intends to convey with their words, as well as how their counterpart in the conversation perceives the words. Machine learning is built on large amounts of data, which can only be processed by Artificial Intelligence. Global networks and cluster analyses are required, both of which are currently being developed at an extremely rapid pace.

The second pillar, or basket, of the Peace Machine analyzes how emotions affect our

decision-making. Honkela asserts that our emotions are a catalyst for human behavior. Aided by large amounts of data, we can learn more and analyze our emotions in various situations, and understand why we react how we do. The limbic system, where our “emotions are born” in the brain, colors our perception of the world. Some traumatic experience can, much later on, affect my reaction without my being aware of it, and may

result in disproportionate actions. The Peace Machine–which is not a computer, but rather, millions of computers collaborating together, with knowledge of individuals and structures–warns me of my own reactions, or helps me to understand how the other party feels, and thinks.

The third basket advances justice in society. Honkela is the scientist with a great

humanitarian and utopian dream. In a conversation in June, he laconically stated: “it isn’t utopian, it’s actually a plan”.

When Honkela published his book in the spring of 2017, it was because he knew that he would die within the foreseeable future, as he had been diagnosed with an incurable brain tumor a few years earlier. Time was running out, and he partially lost his sight after a brain operation, and his memory was damaged. Aware of his life about to end, within a maximum of a few years, he then chose to create the summing up of his life, which he had originally planned to do, once retired, and with the authority brought on by an advanced age; and using more of his creative imagination than that of scientific facts. Honkela sketches out how artificial intelligence could be used to create peace on Earth.

Incidentally, in the book, versions of the word human are the words which appear most often, more in fact than artificial intelligence, machine learning or computers. It is not a scientific book, not in its traditional meaning. Honkela has researched language, but has also researched artificial intelligence and machine learning, among others. Being a counter-disciplinarian is merely the introduction to his voluminous curriculum, in which cognitive linguistics intertwine with psychology, sociology and philosophy. Natural science meets humanism. Somewhere, out of all of this, he creates the three pillars which support the peace machine: language and its meanings, the power of emotions, and a society built on the idea of justice.

It is neither science fiction nor any images of all threats, in all of their forms of terrorism, world wars, natural disasters or mass unemployment that he wishes to delineate. His motive with the book is peace and light and convincing us that artificial intelligence can help us in the reconstruction of all of this–if we desire it. Honkela speaks a great amount about the role of art–especially that of music. It’s a way for him, the human, to understand things beyond their science.

“Aided by art, we have been able to examine that which has to do with emotions, when other disciplines have had a point of view which has been too narrow” (From The Peace Machine, my translation).

This is, in fact, what Martinson does in Aniara: an Epic Science Fiction Poem. In the one-hundred and three songs, he opens up horrific events and actions–for us to be able to understand what we already know.

After the Trinity test, the first nuclear weapons test, Oppenheimer quotes the god Vishnu, from the holy text of Hinduism, the Bhagavad Gita. When mundane words fail us, we need a literary act of ascension:

Now I am become Death, the Destroyer of worlds.

Text: Dan Henriksson

Translation from Swedish to English: André Sumelius

Originally published in HBL, on January 13th, 2019